Is Flickr a place for a professional photographer to display his work and sell images? Todd Klassy thinks so. Though now he is an amateur devoting three hours a week to shooting and another six to post production and studying photography, he intends to quit his job of 17 years and start working as a photographer full-time after the first of the year.

Klassy is 42 years old and has been submitting to Flickr since 2005. He has more than 1,600 images in his primary account, but he acknowledges, “many of them aren’t what I now consider ‘good’ photographs.” He shoots with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II, Canon EOS 1D Mark III and a Canon PowerShot G11.

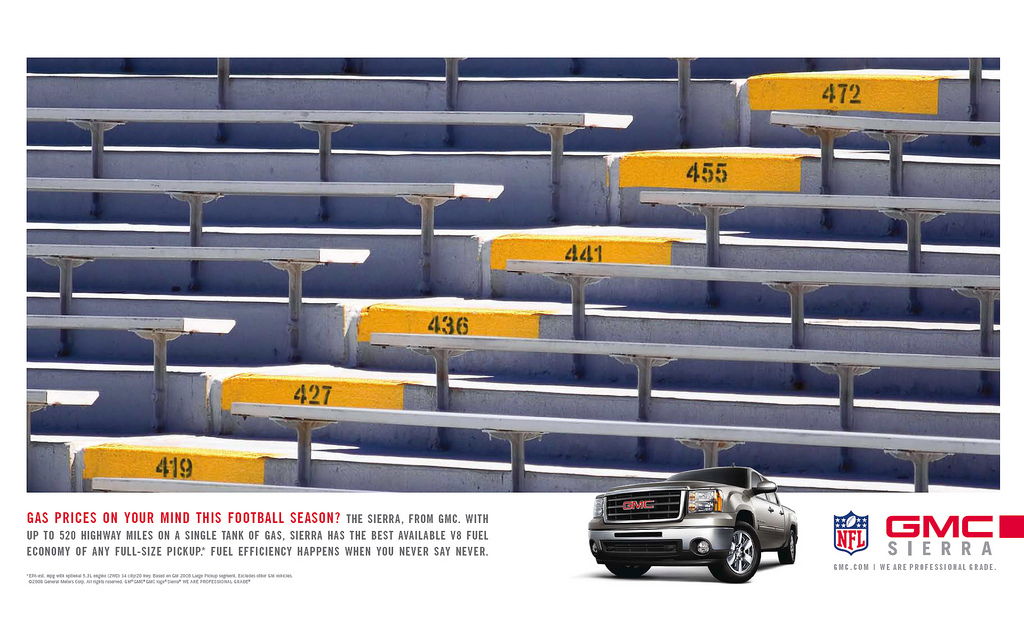

In 2008, Klassy earned over $20,000 from licensing rights to his images on Flickr; 2009 has been better. In 2008, Leo Burnett paid $10,000 to license one of his images of football stadium bleachers for a General Motors ad.

Klassy also has 81 images in the Getty Images’ Flickr Collection, but his “Don’t Be A Sucker” post in the discussion section of the Getty Images Call For Artists Flickr group shows that he is not convinced that an alliance with Getty Images is a good thing for Flickr users.

Klassy also has 81 images in the Getty Images’ Flickr Collection, but his “Don’t Be A Sucker” post in the discussion section of the Getty Images Call For Artists Flickr group shows that he is not convinced that an alliance with Getty Images is a good thing for Flickr users.

When asked what motivated him to take the bleacher image, Klassy said: “When I took it, I had not really studied composition. I knew that patterns and lines were good, but I can't tell you exactly why that image stuck out. When the Leo Burnett art director contacted me and told me the agency wanted to use one of my images, I was excited. But when she told me which one, I was disappointed, because I hated the image. I was stunned. I always try to post my best images, but looking back, many aren’t very good. Luckily, the bleachers photograph, which I consider a generally poor shot, was one I decided not to take down.

“The art director told me they were only willing to pay standard stock photography rates, which to me (at the time) meant iStockphoto Wal-Mart prices. I was working on a project in my office when she called and had her on speakerphone. I said, ‘Well, how much is that going to be?’ I was thinking $200 to $300. She told me it would appear in Sports Illustrated, Sporting News, and ESPN The Magazine, which impressed me, but because I hated the photograph so much and thought it was very pedestrian, it didn't phase me too much.

“She then asked how much I wanted. I said I never give prices first. She then said $8,000, which was later increased to $10,000 when they also purchased Web usage rights. I was floored. I stopped typing and hesitated, but didn't want her to know I was shocked. I finally said, ‘That sounds fair.’ When I hung up the phone the first thing I said was, ‘Damn, I left money on the table.’”

There are several lessons here.

First, it is highly unlikely that Getty, or any other major stock agency, would ever have accepted this image into its collection. But the art buyer saw how it could work for her. It should remind us that the images agency photo editors select are not always the images customers want to buy. Klassy believes that one of the many advantages of Flickr is that the photographer controls the images that get posted.

Yes, he probably did leave a little money on the table, but if Getty had licensed the image, the agency they would have taken 80%, and Klassy’s share would not have been anything close to $10,000. So both Klassy and the client ended up better off.

It is also interesting that Leo Burnett, one of the top advertising agencies in the world, did not go to Flickr because they wanted something cheap. They were willing to pay standard rates. They were looking for something they had not found anywhere else.

The fact that a major art buyer used Flickr is not a fluke. Recently, a British photographer reported that he had made sales to Deutsche Telekom Europe, 12 Nature Trusts around the U.K., T-Mobile, Aspect Tiger productions (part of channel 4), the Guardian News Agency and BBC Media City. Buyers are going Flickr to look for something different, not necessarily to save money.

The best thing Klassy said was, “I never give prices first.” Later, he told Selling Stock, “A wise salesman once taught me to laugh no matter what the other side offers, and then say, ‘Oh, you’re serious. Well, let’s talk.’”

Considering his success at selling directly and Getty’s acceptance of his images, it is interesting that several years ago, Klassy’s photos were rejected by iStockphoto. When iStock showed no interest, Klassy made no effort to contact other microstock agencies and concentrated on selling his images through Flickr. iStock probably did him a big favor.

Not counting the $10,000 sale, Klassy earns an average of $140 to $150 for every image he has licensed. In the three months ending with September, Getty has made 11 sales of Klassy’s work, for a total of $1,513.36, averaging $137.58—less than the average he is selling photographs for on his own. But since Klassy is only getting a 20% cut of the license fee, his average return per image licensed through Getty is $27.52.

Klassy says: “Getty is proving that they are poor salespeople. They are selling images online for $5 for Web usage, when I’ve been able to get $20 to $50 for the same image and same usage! I don't trust them to sell my images for what they are worth and I don't like the lack of freedom I have when they own the rights to market my images for two years. What if I want to give one away to a charitable organization? Under my current contract, I cannot.

“When I signed up,” he adds, “I was lead to believe Getty would only sell premium photographs at a premium price. It was only after I signed up that they unveiled microstock pricing, and more recently their Premium Access Licensing, which is equally bad, if not worse. This is what I’m most upset about.”

Some readers will be quick to note that if Getty were to make 5 or 6 times the number of sales, Klassy can make dealing with customers directly, he could earn more in total dollars, even though the amount per sale would be much lower. Klassy thinks this is unlikely. He is much more interested in maintaining reasonable prices for his work than in selling volume.

One thing Todd has to deal with is requests from people who want images for free. He says about half of all requests come from people who do not want to pay. But this is offset by the fact that his images can be found by all major search engines. He generally asks customers how they found him, and about half of the requests result from Google searches.

Part of the traditional rationale for placing images on multiple sites around the world is the theory that when it comes to finding photos, customers use many different sources. Therefore, the best way to ensure that your photos will be seen is to have them everywhere. This may be 20th Century logic. Klassy believes that most customers will go to search engines to look for photos. By making it possible for your photos to be found by those using all the major search engines, you have the potential to reach all customers. Thus, instead of posting your images on many sites, optimize your collection so it can be found on search engines. If the industry is not at this point yet, it may be where it is headed.